By: Andrew Evans aka The Pickleball Librarian

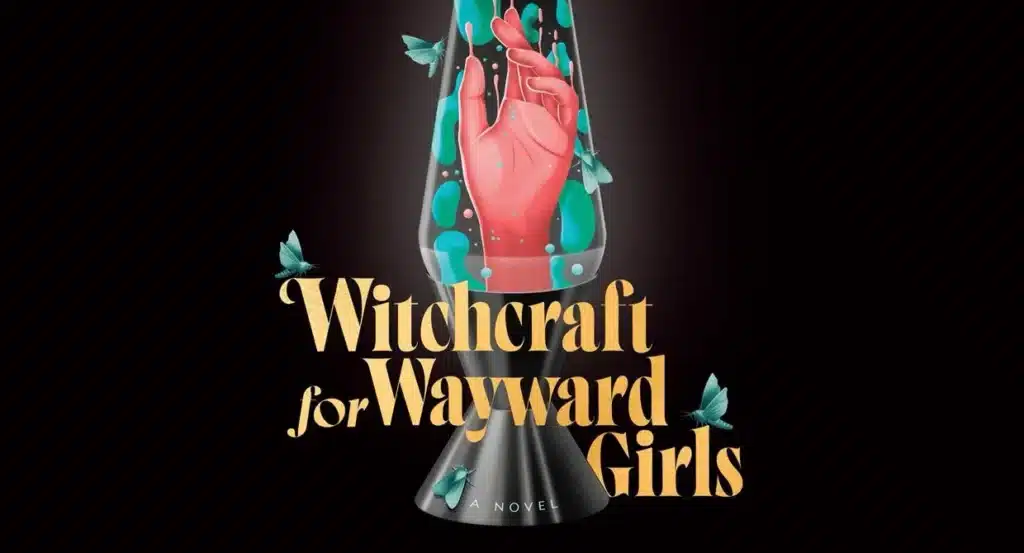

I often say that horror is just a vehicle to convey a deeper message or story. Grady Hendrix does exactly that in Witchcraft for Wayward Girls. The story takes place a couple of years before Roe v. Wade.

Grady had a couple of relatives who spent a few months in maternity homes but never spoke about it for nearly 50 years.

“I grew up with these two women and loved both of them very much. For years, I tried to understand what they had been through, but I couldn’t wrap my head around how scared and isolated they must have felt. I tried to imagine what it was like to have a child but not know if they were alive or dead, sick or well—and I couldn’t. So I did what I always do when I can’t figure something out: I wrote a book.”

It’s heartbreaking to think about this lonely experience, and the book brings it to life. Many of these pregnant girls—yes, a lot of them were under 18—were terrified. Their families treated them differently. They were ostracized, kicked out of school, and called all sorts of names. As a result, many families sent them to temporary maternity homes and simply made up stories about where the girls had gone.

These families often told others, including their own siblings, that the girls were visiting a cousin or studying somewhere else. While in these maternity homes, surrounded by strangers, the young women had no control over their bodies or lives. They were told what to do, what to eat, and when to sleep.

I also feel the deep pain of choosing between giving a baby up for adoption and trying to raise it alone in an era when single mothers were heavily stigmatized. Back then, maternity homes often prevented unwed mothers from even holding their babies after giving birth, fearing they might change their minds. After all, adopting families typically covered the costs of delivery, room, board, and other expenses for the expectant mother. Should a young mother keep the child that came from her own body, or should she give them up for adoption? That is a choice no young woman should have to face alone.

The Story

The novel takes us into this world. The girls are forced to use fake names and claim they are from different states so no one will recognize them and their families won’t be embarrassed. In this case, Neva becomes Fern.

Grady introduces a large cast of characters in this book. At first, I started writing a list to help keep track, but I recommend focusing on a few key figures: Fern’s roommates, the employees of the wayward home, the librarian who gives Fern How to Be a Groovy Witch, and, of course, the witches themselves. The witches promise Fern and her friends a way to take back their autonomy—but fail to mention the steep price they’ll have to pay. Once again, the girls are faced with another impossible choice.

The book delivers suspense, especially during the chase scenes. Readers will find themselves staying up late, hoping the witches don’t sneak in. There’s also a good amount of body horror, and the scenes involving witchcraft build anticipation as you wait to see the results of each spell.

Grady captures and conveys feminine rage exceptionally well. Reading this book serves as a stark reminder that the best thing about “the good old days” is that they’re gone. At one point, we had about 190 maternity homes for unwed mothers across 46 states, run by organizations such as the Florence Crittenton Mission, the Salvation Army, the Catholic Church, and independent operators. After Roe v. Wade, these institutions largely disappeared.

This book takes us back to a dark chapter in history. Back then, young women were expected to bear the burden of pregnancy alone, while their male counterparts’ futures remained untouched. I highly recommend this book because we cannot forget the past. We must remind ourselves: We won’t go back.