A Reflection on the Borders We Build and the Walls Within Us

At the southern border of this nation, the desert stretches wide and merciless beneath an unforgiving sun. The Rio Grande winds like a scar across the land, a line not of geography, but of policy and power—where skin tone often dictates freedom or confinement.

From afar, cities like El Paso and San Diego gleam with the promise of opportunity. Tourists post photos of their tacos and sunsets, and politicians boast of economic might. But just beyond the glimmer, in barbed-wire camps and tent courts, thousands of men, women, and children sit—awaiting judgment, praying for mercy, or sometimes simply waiting for time to run out.

As I stood on a hill overlooking one such camp, they pointed toward the razor-wire fences below and said:

“That’s where we keep the migrants. That’s the holding facility.”

The words hung cold in the air.

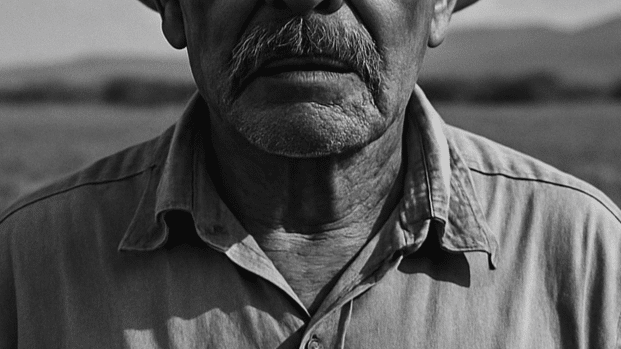

There, locked away, were asylum-seekers and refugees—farmers and nurses, children and dreamers—all caught in the machinery of a nation that has forgotten its own immigrant heart.

These camps are not exceptions. They are monuments to our collective failure to see humanity in those we call “other.”

And so I asked, not as an activist or a politician, but simply as a human being:

“But suppose God is brown.”

Suppose we reach the gates of Heaven after lives spent building walls, passing laws, and locking doors—and God is standing there, not with pale skin or blue eyes, but with brown skin, eyes dark as rich soil, and hair curled under the sun. What then will be our defense?

What will we say to explain the children we caged, the families we separated, the workers we exploited—those we called “illegal,” while they toiled in fields to fill our tables?

What will we say to a God who speaks Spanish, who crossed borders Himself seeking shelter as a refugee in Egypt?

Silence will likely be our only answer.

Today, our national dialogue circles endlessly around “security,” “law and order,” and “sovereignty.” The words are sterile, but their consequences are not.

In the name of safety, we spend billions to militarize borders, but pennies on the schools where immigrant children sit hungry, too afraid to speak their mother tongue.

In the name of jobs, we demonize the laborers who pick our fruit, clean our hotels, and build our homes—often paid less than minimum wage, with no voice to protest.

In the name of faith, some still preach exclusion, saying God’s kingdom has locked gates and high fences—that there are front rows for some, and standing room only for others.

But what faith is that? What scripture teaches cruelty to the stranger?

In communities across this country—from border towns in Texas to farms in Kansas—the question is no longer simply political. It’s spiritual.

Do we believe every person bears the image of God? Or only some?

I think of a mother I met in a migrant shelter, who had fled violence in Honduras with her two children. She carried nothing but a Bible and a battered backpack. In broken English, she said:

“I have hope, because God walks with me. Even if your country does not want me, God wants me.”

That night, I lay awake and thought: She might understand the Gospel better than most of us.

In the end, this is not about immigration alone. It is about whether we see dignity in every person who crosses our path—whether they wear a business suit or a border patrol uniform, whether their skin is brown, black, white, or anything in between.

Because every act of cruelty we permit today will return to us tomorrow—in our politics, in our streets, in the quiet of our souls.

Suppose God is brown.

Suppose He is the migrant at our gates, the janitor in our schools, the man selling fruit on the corner.

Suppose the face we have feared is the face of the Divine.

Will we have the courage to look Him in the eye?

Or will we, too, fall silent?

“The test of our humanity,” I imagine Robert F. Kennedy would say today, “is not how we treat those who look like us—but how we treat those who don’t.”

The question remains.

How will you answer?